Accelerator for America – Update on Infrastructure Implementation

How Cities & Metros Are Organizing for Federal Infrastructure Funds

Since the passage and signing of the infrastructure bill, we have continued to engage with mayors and their offices across the country to prioritize the legislation’s funding opportunities. This is the first of a series of bulletins to share how cities of all sizes and governance structures are approaching Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to surface lessons learned and identify best practices to inform decision-making nationwide.

Background

To provide immediate assistance to cities, Accelerator for America created our Federal Investment Guide for Local Leaders. Our guide gives city leaders a streamlined manual to funding opportunities best suited for the city or regional level. The guide was created in partnership with the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, the US Conference of Mayors and the Oxford Urbanists.

Our guide complements the White House’s Guidebook to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This guidebook provides a comprehensive list of programs funded by the bill, as well as a convenient downloadable spreadsheet, making it easy to identify the full range of competitive funding opportunities and estimates on when notice of funding opportunities (NOFOs) will be live.

Our Federal Investment Guide provides city leaders with six key strategies to better prepare themselves to move on BIL programs:

Strategy 1: Approach BIL Funds in terms of applicants and recipients

Strategy 2: Engage private financing using infrastructure as a platform

Strategy 3: Build economic opportunity through deployment

Strategy 4: Geographically align spending to support place-making

Strategy 5: Use the BIL to address the climate crisis and build resiliency

Strategy 6: Position your city as a clean energy and tech innovation hub

Early Lessons from First Mover Cities & Metros

Strategy one, listed above, is an essential first step all cities must take to identify which BIL programs to pursue, the local, regional, and statewide partnerships to develop to better position themselves for formula and competitive grant funding, and the federal agencies and programs best aligned with their priorities. Taking advantage of the opportunities funded by this law requires large amounts of staff time and resources. All cities struggle with staffing and resource constraints, requiring them to be clear-eyed in prioritizing what competitive funds to pursue and which formula grants to deploy in a coordinated fashion. This endeavor looks different in every place. No two cities are alike nor face the same slate of challenges or build from the same strengths. So, while the objective remains the same, the pathways to getting there remain as unique as the cities themselves.

Below we highlight six key lessons we have learned from speaking with first mover cities and metros across the country.

Lesson 1: One of the simplest and most effective early steps mayors and county leaders can take is to appoint a dedicated infrastructure coordinator.In conversations with cities, an emerging theme we observed is that places with dedicated coordinators and conveners are more organized overall than those without clearly established leadership. Many places are still in the process of setting up clear coordination mechanisms across local entities as federal programs are defined. Designating an infrastructure coordinator is a way to jumpstart this process. Coordinators serve multiple functions, track and communicate funding opportunities, mobilize coalitions and capacity around large grant applications, and serve as a liaison across public authorities and administrative departments.

Lesson 2: While many metros are establishing new models for collaboration, no single model exists. Cities are developing innovations to solve unique problems.

San Antonio, Texas developed a cross-agency infrastructure task force led by the city manager and mayor.

After signing the BIL, President Biden issued an Implementation Executive Order outlining six implementation priorities federal agencies must follow when considering and allocating the law’s funding. Mayor Ron Nirenberg used this Order, coupled with Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s January 4 letter to the nation’s Governors, as guiding lights for his own implementation philosophy. Mayor Nirenberg appointed City Manager Erik Walsh as San Antonio’s Infrastructure Coordinator. In parallel with the White House, Mayor Nirenberg and City Manager Walsh created their own “Infrastructure Implementation Task Force'' through an Executive Roundtable composed of CEOs from public agencies and authorities from across the region. The task force includes leadership from Bexar County, VIA Metropolitan Transit, Joint Base San Antonio, the Texas Department of Transportation, the Alamo Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), the San Antonio River Authority, Port San Antonio and several others.

The task force meets on a bi-weekly basis to coordinate and create linkages wherever possible. City Hall staff and their federal lobbyists quickly created a presentation to distill and communicate the essential data of what was in the BIL to the city’s department heads and leadership.

To triage their efforts around programs, the city developed a BIL Program Tracker cataloging each of the legislation’s programs of interest to the city. In addition to this information, the tracker catalogs the local offices and agencies of jurisdiction, city projects eligible under a given program, and potential internal and external partners. The city initiated a dialogue with state officials and their state legislature delegation early on to ensure the city’s needs were communicated.

Louisville, Ky. established a Stimulus Command Center led out of Metro Hall. Local governments in Kentucky have limited revenue authority and are overly reliant on funding decisions from the state government. This places Louisville at a disadvantage when applying for the BIL’s competitive grant programs because of non-federal match requirements. So, while the city still plans to pursue competitive grants, Mayor Greg Fischer and his staff are creatively planning for competitive BIL opportunities. For example, the city, in collaboration with Accelerator for America and the Nowak Metro Finance Lab, is building off of its Stimulus Command Center (“Louisville Accelerator Team”), which was created to intake and invest American Rescue Plan funding to prepare for this historic infrastructure investment. In addition, the city of Louisville is onboarding a dedicated infrastructure coordinator and leveraging consultant groups to bring on grant writing teams to increase staff capacity.

Tacoma, Wash. built a cross-department working group & the mayor is appointing an infrastructure coordinator. Mayor Victoria Woodards is leaning on her Government Relations and Public Works teams to organize the city for BIL opportunities and is looking to appoint an infrastructure coordinator in the near future. In the meantime, the city has established a working group across city departments and agencies including Metro Parks Tacoma, Port of Tacoma and several neighboring cities, ensuring internal entities and external partners are aware of and coordinating with each other’s priorities and efforts. One of the major stressors on local infrastructure––that the working group is focused on addressing–– has been enormous population growth since the onset of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan due to the proximity of Joint Base Lewis McChord and more recently, local housing affordability in comparison to the Seattle metro area. Moving people and goods is critical to the local economy. The city has partnered with the Port of Tacoma, the Puyallup Tribe of Indians and neighboring cities to address structural needs of the Fishing Wars Memorial Bridge, an important commercial arterial linking Tacoma to the Port of Tacoma’s industrial center, the largest job center in the South Sound. The task force meets on a bi-weekly basis to coordinate and create linkages wherever possible. City Hall staff and their federal lobbyists quickly created a presentation to distill and communicate the essential data of what was in the BIL to the city’s department heads and leadership.

Lesson 3: Cities cannot act alone, Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) are an essential partner for making big impact with the BIL.

Mid-America Regional Council (MARC) is the Council of Governments (COG) / MPO for the Kansas City region. Since MARC represents one metropolis spanning two states, Executive Director David Warm and his team must coordinate funding priorities across two state governments, two big-city governments and a host of smaller local government entities. Among MARC’s key priorities is the development of the Bi-State Sustainable Reinvestment Corridor based on the success of the Green Impact Zone in Kansas City, MO that aligned federal and local investments between 2008 - 2013. MARC also coordinated the submission of a timely proposal for the Economic Development Administration’s Good Jobs Challenge focused on manufacturing, construction and the skilled trades. MARC is working closely with Congressional representatives, mayors and county leaders in Kansas and Missouri to advance these priorities.

The Maricopa Association of Governments (MAG) is the greater Phoenix region’s MPO and encompasses a large region including Phoenix, Mesa, 25 other cities and towns, and three tribal nations. MAG is working to bring the Arizona Department Of Transportation (ADOT) deeper into the region’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure implementation and is coordinating a coalition of the City of Phoenix, Arizona Corporation Commission, Arizona Forward and others, to move forward when ADOT is ready.

Lesson 4: Cities and metros are contemplating ways to raise local revenue to supplement and complement new federal investments.The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is serving as a catalyst in many places, which are responding by seeking additional public funds through ballot measures so they can leverage federal funding and better target it to local priorities. In a future piece we will be exploring the mechanics of how these local funds interact with federal sources.

Maricopa County, Ariz. is in the midst of a 2022 ballot measure campaign to renew a ½ cent sales tax for the next 25 years, which will be critical to the expansion of the region’s public transit systems.

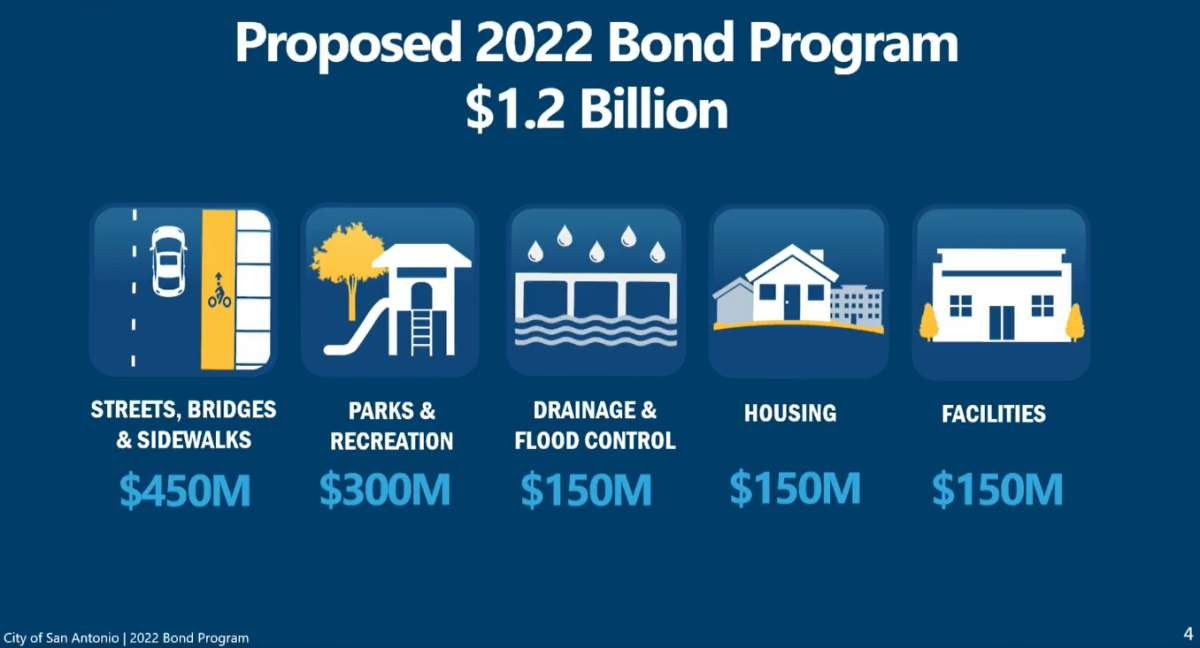

San Antonio is putting a $1.2 billion municipal bond package in front of voters in May 2022. This package is largely dedicated to basic infrastructure. The package includes $472 million for streets, $272 million for parks, $170 million for drainage and $136 million for public safety, library and cultural facilities upgrades. City leaders are using community engagement around this bond package to identify priority projects that will have linkages to other infrastructure investments supported by federal funds. The city intends to use the bond for smaller projects that are more difficult to finance with federal funding.

Voters in Boise, Idaho approved a $570 million water bond in November 2021 that was critical to the city receiving its first ever Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) loan from the EPA for $272 million. The federal loan will supplement the local funding sources to improve water quality and reduce sewer fees.

Lesson 5: On the whole, states and metros are better prepared to absorb transportation funds but are working to build coordination capabilities around newer areas of funding. MPOs and state DOTs have a long track record that prepares them to coordinate and strategize around surface transportation funds. However, newer funding sources, including broadband and new resiliency programs, don’t necessarily have the same pre-existing regional networks to organize their deployment. State structures governing broadband planning and funding vary widely. Even within transportation, some newer funding sources, such as those for the installation of electric vehicle charging stations, will require a new level of cooperation among state transportation departments, environmental departments and grid operators to oversee installation, a process that will be hammered out in the coming months and years.

Lesson 6: Building out workforce capacity to meet the market-demand created by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law requires focused partner coordination. In a moment with such a tight labor market, local leaders from rural and urban areas alike are grappling with how to build a diverse and adequate pipeline of workers and firms to deploy projects. From pipe- and wire- laying, to weatherization and architecture, to maintenance, the jobs and businesses created to meet this demand require a broad range of skills. City and metro governments must work closely with partners –– workforce boards and other workforce intermediaries, unions, chambers of commerce, and trade associations–– to connect workers to jobs and firms to contracts. Crucially, State and Local Fiscal Relief funds from the American Rescue Plan can be used for these workforce needs. Groups like the North America’s Building Trades Unions (NABTU) oversee apprenticeship and apprenticeship readiness programs that meet this workforce need. How can your city work with your local unions to create or scale their existing programs? ARPA funds can be used to fund these low-dollar, high-impact programs.

Emerging Issues

As we spoke with cities and metros around the country, we also became keenly aware of issues that have not yet been resolved. In the coming weeks and months, finding actionable solutions to these issues will be a key priority of the Accelerator. Please share your great ideas so we can feature you in a future bulletin! info@acceleratorforamerica.org

Emerging Issue 1: Local leaders want to ensure new BIL funds are spent in service of broader economic development, but face challenges. Leaders on the ground in cities understand that infrastructure is a physical investment that structures the broader set of economic opportunities available to communities, cities and regions. Cincinnati, OH would like to use additional EPA brownfields funds from the BIL to acquire and develop brownfield sites for new advanced manufacturing. However, as currently written, the program provides funding for demolition and clean up, but does not fund acquisition and transformation, stunting the overall economic development impact of the program. Harmonizing the compatibility of multiple federal sources will be vital for broader impact. Further, as competitive grant programs roll out, some with high dollar matching requirements, we will be monitoring for the impacts on equitable distribution of these funds; higher poverty cities will struggle to meet match requirements, and this threatens to only further the economic divide in America.

Emerging Issue 2: The largest cities have significant in-house capacity to organize and plan, giving them a distinct advantage. While many larger cities have enough city hall or departmental staff and contractors to strategize for a wide variety of competitive U.S. DOT and other grants, many smaller places do not. This often leads to a geographical inequity in federal funding awards. Addressing this challenge for smaller places requires the following: (1) a clear prioritization of competitive funds to pursue; (2) a clear-eyed understanding of what specific capacity is needed (our partners at Drexel identified key capacity needs in a recent memo), and; (3) fully utilizing capacity in the nonprofit, private and civic sector to help backfill the capacities that the public sector may not have immediately available.

For our latest updates on our work and latest insights from cities across the country, make sure you join us on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

We appreciate your support and your commitment to creating national change from the ground up.

Thank you for all that you do.

Mary Ellen Wiederwohl

President and CEO | Accelerator for America